Explain like I'm five: Cryptographic Hashing

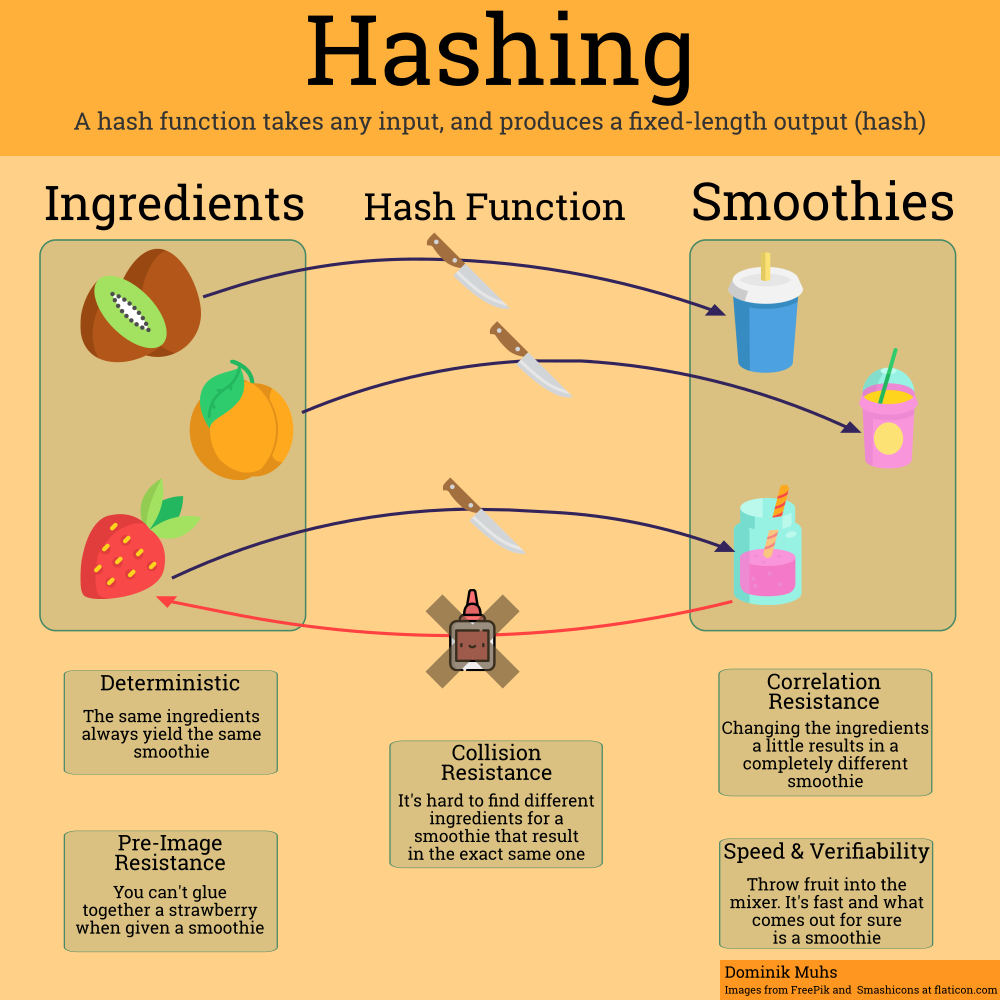

tl;dr Just check out the image and read the details below it if you want to know even more. :)

A few days back I read an article by Yunyun Chen explaining Hashing in an infographic. I enjoyed it and read some comments, which pointed out a couple of weak spots that result from common misconceptions about (cryptographic) hashing.

Mostly this is a result of the distinction between the concept of a cryptographic hash function (its formal, mathematical properties) and implementations of that concept (concrete algorithms such as SHA-256). As the blockchain community attracts people from all kinds of backgrounds, it’s important to clarify these former and educate people about the basic cryptographic concepts blockchain technology is based on. Only when a community around a technology is educated about how it works it can make meaningful progress and ultimately create innovation.

That said, here is my take on a fresh infographic about hashing, meant for people without much prior knowledge:

While the list of properties is by no means exhaustive, it should give a decent impression of the basic properties a conceptual hash function has. If you want to know a little more, here are some explanations that dive a little deeper (and further away from smoothies and fruit):

Determinism

This is one of the most straightforward properties. Throwing a strawberry into a mixer will always result in a strawberry smoothie. With only strawberries, you won’t be able to make a peach smoothie. Similarly, for a certain value you throw into a hash function, you will always get the same hash value.

It is important to note here that this relates to reuse of the hash function. Concrete implementations use a (pseudo-)random value for initialization ("seed"), which can vary each time the hashing function is instantiated. A simple example is Python’s hashing function. It is seeded every time you start a Python process.

In [1]: hash("foo")

Out[1]: -6427459509433145349

In [2]: hash("foo")

Out[2]: -6427459509433145349

<restart Python process...>

In [1]: hash("foo")

Out[1]: -7165618396328893146

In [2]: hash("foo")

Out[2]: -7165618396328893146

We can easily see that the string "foo" is mapped to the exact same value, which means the hash() function satisfies the deterministic property, however once we restart the Python process and try again with the same value, it is different. This is due to the fact that the seed value has changed. If we reuse the function in the same process again, we still get the same value. Similarly, imagine a mixer that changes the smoothies every time you turn it off and on again.

Pre-Image Resistance

Fancy name, easy concept. When given a hash value, it should not be feasible to infer the data that resulted in that value. The equivalent would be if an attacker tried to glue to smoothie back together to the specific fruit it was created from.

The only possibility that an attacker should have is to try all potential inputs — where no input is more probable than the other one. This basically means that an attacker must not be able to gain any information from a given hash. In formal wording the result of a hash function is called an image. The input value resulting in that image (what comes before) is called the pre-image. Cryptographic hash functions must be robust against these kinds of pre-image attacks by making them unfeasible.

Correlation Resistance

This is often mistaken for pseudo-randomness or thrown in the mix with other concepts. The formal term here would be called the Avalanche Effect. This means that a slight change in the input (turning a 0 into a 1 in 20TB of data, or adding a slice of lemon to a ton of strawberries) should accumulate like in avalanche triggered by a small snowball and in the end result in the whole output being changed (and the whole smoothie tasting differently).

From an attacker’s standpoint, this makes it impossible to gain information by observing lots and lots of hashes (or checking out tons of smoothies). If there were a systematic change in the hashed data (or the smoothie always tasting a little more sour), an attacker could infer information on the input data. This would allow them to make predictions on the input data even though they only see the hashed output (slightly more sour smoothies). In the worst case this can completely break the function and allow an attacker to find the pre-image for a given hash. If you’re interested in how this is avoided in practice, check out the beautiful field of chaos theory, especially the Butterfly Effect.

Collision Resistance

A hash collision is exactly what is sounds like: Somewhere behind the hash function a crash occurs. Specifically, this relates to two different messages resulting in the same hash (or two different ingredients resulting in the same smoothie). Most famously this is what happened to SHA-1 in February 2017 when some (really cool) researchers found such a collision (in itself not a big deal) and made it practically usable (really big deal).

Speed and Verifiability

We are still abstracting from concrete implementations here. The speed property relates more to the computational complexity of the algorithm. Even for large amounts of data it should be quick to compute (making a smoothie from a ton of strawberries shouldn’t be much slower than making a smoothie from just one). That’s the way from our message to its hash value. On the other hand, let’s say we have received a hash value and want to verify that a message we hold results in that hash. Easy: We can calculate the hash for our own message and compare it to the one we have received. Speed+Determinism=Verifiability.

A Short Note on Fixed-Length Output

This is often sold as a property of cryptographic hash functions. This might be up for debate between hardcore cryptographers, but I do not see anything against a hash function that outputs results of variable lengths. This would not eliminate any of the above properties (or the ones I have not mentioned here because I want to write a blog post, not a book). In fact, there even seem to be cryptographic hash functions realizing this behaviour, called sponge functions. I have just recently learned about this, however and I do not feel comfortable enough writing about it just yet.

To All Who Have Read Until Here in One Go

You are either already familiar with cryptography or really eager learners. In any case, you might appreciate the free Coursera courses of Dan Boneh for Cryptography I and II. They take a while and are kept quite academic, but there is nothing to be afraid of.